When it comes to sport in Taiwan, the famous names that spring to mind are probably Yani Tseng, the LPGA golfer with five majors under her belt, or Wang Chien-ming, a pitcher formerly with the New York Yankees. But to a different generation in Taiwan there is one figure who stands above all others. Sports Illustrated named him the “World’s Best Athlete” and others feted him as the “Iron Man of Asia”. He was Taiwan’s first Olympic medalist. His name? Misun Kalimud, better known to the world as C.K. Yang.

Like a disproportionately high number of successful sportsmen and women from Taiwan, Yang was an Aborigine. A member of the Amis tribe, he was born in Taidong—the poorest, most isolated county of mainland Taiwan—in 1933. Yang grew up in Taidong City and though he was a national champion in his age group in the high jump, he was not considered a great athletics prospect at high school, and was criticised by his coaches for not taking direction well. From there he went to Hualian for military service, a rite of passage dreaded by most young men, but one which proved to offer great opportunities to the young Yang. With access to better faciliities and coaches in the army academy he improved, but his performances were still patchy despite his obvious talent.

The dividing line between his early period of unfulfilled promise and the success of later years came in 1954, at the Asian Games in Manila. With his consistency improving in the run-up to the Games he was entered in the decathlon despite being weak in the throwing events. In the event itself, his performances on the track and in the jumps were so far ahead of his competitors that he was able to take the gold medal, his first major triumph. The Taiwanese media hailed his success, calling him the “Iron Man of Asia”, and Yang was subsequently given access to the best training facilities the government could provide for him. By the time of the next Asian Games, in Tokyo in 1958, Yang was the overwhelming favourite for the decathlon. He duly won the gold medal with some distance to spare, and for good measure also competed in individual events, winning two silvers in 110 metre hurdles and the long jump, plus a bronze medal in the 400 m hurdles.

By this stage in his career Yang had outgrown the training environment at the time, and needed new challenges to develop his potential. He moved to UCLA in the United States, a university renowned for its athletics facilities and home to Rafer Johnson, the preminent American decathlete of the day. Johnson had won silver in the 1956 Olympics when gold had looked a certainty after dropping out of one event through injury, opening the top spot on the podium for his compatriot Milt Campbell. After the Games Campbell retired from athletics and became an NFL player, leaving Johnson as the biggest name in the decathlon and the favourite for gold at the 1960 Olympics in Rome.

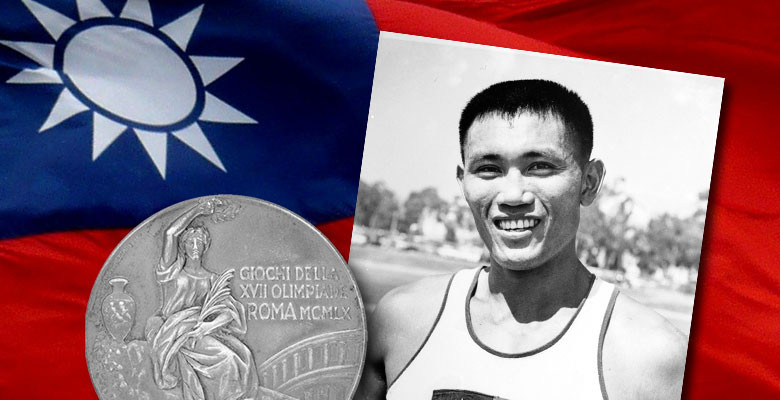

Johnson and Yang were great rivals in sport, and became enduring friends off the track. The Games in 1960 were the climax of both their careers. Johnson was far ahead of Yang in the shot and javelin, and while Yang had come out on top on the track, Johnson held a small points lead going into the final event, the 1500 m. Although Yang beat Johnson over the distance, Johnson’s time was good enough that he held on to claim overall victory and the gold medal. Yang had to settle for silver, the first ever medal won by a Taiwanese athlete at the Olympics.

Yang remained in the US after the completion of his studies, and continued competing in the decathlon. In 1963 he achieved the remarkable feat of breaking the 9,000 point barrier in the decathlon, the first man to do so, in the process becoming the world record holder. On paper he looked like a great prospect for the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo, but finished in a disappointing fifth place. Yang claimed that during the event a fellow competitor from the ROC team, Ma Ching-shan, gave him a cup of orange juice. Later that evening Yang became violently ill, and was unable to compete to his full potential in the event, leading to him later accusing Ma of spiking his drink to sabotage his chances. The charge was never proven, but Ma absconded from the team and instead of returning to Taiwan fled to the PRC, where he was granted citizenship. This lends some weight to Yang’s claim that the Communists were behind a deliberate attempt to prevent a Nationalist Chinese competitor winning the event. The Tokyo Games offered Yang’s best—and last—chance to win an Olympic gold medal, and after the crushing blow of missing out, Yang retired from the sport.

In later life Yang became a coach of the ROC athletics squad, and eventually went into politics, being elected as a Kuomintang legislator in 1983. On the formation of the Democratic Progressive Party in 1987 he switched allegiances, and stood unsuccessfully as the DPP candidate for Taidong County Commissioner. During the campaign he had attracted controversy by auctioning his Olympic silver medal, with his opponent using the slogan “yinpai wujia”, meaning both “a silver medal is priceless” and “a silver medal is worth nothing”. He turned away from politics, back to the training grounds and the mentoring of Taiwan’s Olympic teams, where he spent the rest of his working life. He died in his adopted home town of Los Angeles in 2007 at the age of 74, from complications of a stroke.

Yang was a colossus in the public imagination in Taiwan, at a time when the country was still relatively poor and the real threat of war hung constantly over the island. He was a bright light amid the troubles of the day, and he is still held in great affection by a great number of older Taiwanese people. There are still buildings and sports fields named in his honour, and Chuanguang Road, one of the main streets in Taidong City, carries the Pinyin version of his name. So, the next time someone mentions the latest Taiwanese baseball player to sign for an MLB side or tennis player to claim a title, you can sigh wistfully and exclaim “yes, but s/he’s no C.K. Yang.”